The moral comfort of not knowing

- 3 hours ago

- 3 min read

Dear Reader,

There's a particular breed of person who considers themselves ethically sound.

They sort their recycling with reasonable diligence, voice concerns about labour practices over dinner parties, and feel a brief flutter of righteous concern when documentaries about supply chains go viral.

They are morally informed, these people. Conscientious, even.

They are also extraordinarily convenient to themselves (WHAT A SHOCK).

This is not hypocrisy, at least not in any melodramatic sense. I mean, they are not twirling moustaches while exploiting the masses.

They have simply been granted the luxury of never having to confront the machinery that sustains their comfort.

And convenience, as it turns out, is a remarkably effective moral anaesthetic.

When ethics had geography:

Historically, morality used to be unavoidably proximate.

You knew who made your clothes, roughly speaking. You understood how long things took to grow, to build, to travel from there to here.

Buying things had natural friction, and that friction taught you ethics.

You could not keep acquiring or consuming endlessly without encountering effort, your own or someone else's, made visible to you.

Modern convenience did not eliminate the effort. It just made sure you no longer saw it.

The great relocation project:

Today's convenience is built on a simple principle: remove any visible traces of labour from the consumer experience.

You do not see the warehouse worker whose bathroom breaks are monitored by algorithmic overseers.

Instead, you see a cheerful dot moving across a digital map. You see updates like "Out for delivery" and "Arriving today," as if your package moved on its own, powered by goodwill rather than economic need.

The interface is built not only to be easy to use, but to feel ethically easy too. The human cost behind it has been polished out of view.

The invention of moral latency:

One of the most underappreciated philosophical developments of recent decades is the one-click purchase.

It is typically celebrated as a triumph of user experience design, but it represents something more consequential: the elimination of what we might call moral latency.

There was once a pause between wanting something and having it. That pause was full of useful interruptions.

Desire now travels at the speed of bandwidth, while ethics still moves at the pace of reflection.

And reflection, it seems, has become technologically obsolete.

Food as weather:

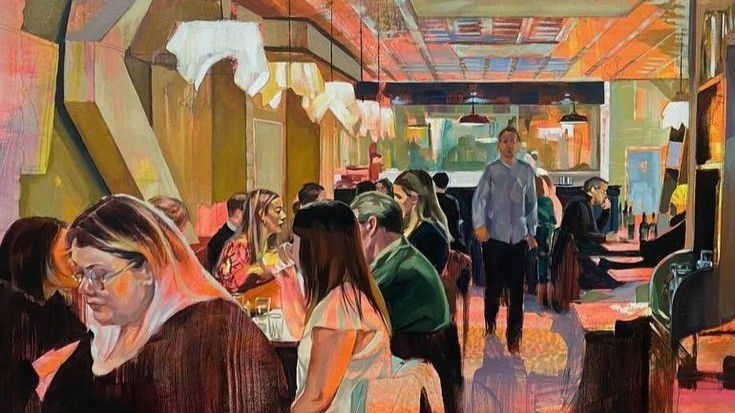

If convenience has a signature achievement, it is food delivery.

Food once demanded a relationship with reality: shopping, chopping, cooking, waiting.

Even takeout required leaving the house, making eye contact, and social interaction.

Now food arrives, like the weather.

You do not see the restaurant's chaos, the thin margins, the kitchen worker's double shift. What you see is a packaging design and a rating prompt.

To you, this feels like kindness, a small mercy extended to your fatigue. To the infrastructure beneath it, it is compressed labour, economic precarity, and an efficiency race against software that never needs rest.

But the interface is beautiful. So the ethics feel resolved.

The stagecraft of virtue:

Convenience does not make systems ethical; it makes them invisible.

If you do not see harm, you do not process harm. If you do not process harm, you do not feel implicated in it.

This is not moral failure but cognitive architecture.

Humans are proximity-based empathisers. We care more about what we witness than what we intellectually understand.

Convenience platforms understand this very well. Everything unpleasant is kept out of sight while the consumer experience remains polished.

The gratitude recession:

The psychological consequences accumulate slowly.

When everything is easy, nothing registers as effortful. When nothing feels effortful, nothing seems particularly valuable.

Patience begins to look like a system malfunction rather than life’s natural condition.

Waiting feels like an injustice rather than a circumstance. Gratitude, which historically grew from effort and delay, finds itself rootless.

Convenience expands expectations while quietly contracting appreciation. Ease, once normalised, becomes baseline. What was luxury becomes entitlement.

The more reality bends to accommodate comfort, the more discomfort feels like a personal affront.

The untested character:

We like to believe our ethics stay the same everywhere, that we would act with equal integrity under any system.

It is a reassuring assumption, though worth examining.

How much of who we think we are morally has been shaped by systems designed to hide discomfort?

Would we consume differently if every purchase forced us to see its full human and environmental cost?

Or have we mistaken comfort for character?

In the end, convenience offers a seductive bargain.

You may live efficiently and comfortably, never confronting the systems that sustain that comfort.

All it asks in return is a small psychological accommodation: that you allow yourself to feel humane in principle while participating, daily and effortlessly, in systems whose full visibility might complicate that self-image.

Cheers!

Akanksha

Comments